Indigenous American ancestry

Learn more about how 23andMe defines Indigenous genetic ancestry of the Americas

Understand what genetic ancestry tests can and cannot tell you

Just as countries have the sovereign right to decide who is a citizen, Tribes within the United States and First Nations within Canada determine membership based on many factors, such as cultural affiliation, residence, community connection, genealogy, self-identification, and language.

Though some Indigenous groups in what is now the U.S. and Canada have used DNA paternity tests in some cases to determine descent from a known ancestor, genetic ancestry tests like those conducted by 23andMe are not used by Indigenous groups to determine membership. Given how deeply held identity can be and the ways that colonial ideas of race have impacted Indigenous sovereignties, it is unrealistic to think that claims about Indigenous American DNA will not impact cultural and political understandings of Indigeneity.

Vast diversity among Indigenous peoples

There are over 570 federally recognized Alaska Native Villages and American Indian Tribes in the United States alone, plus over 630 recognized First Nations governments or bands in Canada, but there are many others in addition to those with federal recognition. In the context of the US, tribal recognition also happens at the state level. In Central and South America, there are more than 700 Indigenous groups, and nearly 50 million people identify as Indigenous.

Frequently Asked Questions

Genetic ancestry tests and Indigenous sovereignties

While we do see some correspondence between the present-day or historical locations of some Indigenous Peoples and these regions, we are not including this information in your results. This decision was made following the strong recommendation by Indigenous subject matter experts, and is additionally based on our current assessment of this update's technical limitations and its potential to impact Indigenous sovereignties.

We explore the reasons for this decision in more detail, below.

At 23andMe, we believe in helping people access, understand, and benefit from the human genome. With this update, we believe that many customers with Indigenous ancestry from what is now the U.S. and Canada have an opportunity to learn additional geographic clues about their ancestry through their DNA.

While there may be some Tribes, First Nations, or Peoples who are more represented in certain regions, the reference groups for these regions were not curated or adjusted based on Tribes or First Nations. For example, some individuals who identify as Cherokee may receive a match to the "South Central" region, while others who identify as Cherokee may receive a match to a different region.

In many cases, the regions in this report likely correspond to the current or historical locations of certain Indigenous Peoples, and in other cases these connections may be less apparent, as major historical migration events including forced relocations have shaped the landscape of genetic variation in what is now the U.S. and Canada. One example of this — resulting from the Indian Removal Act of 1830 — is what is known as the Trail of Tears, which forcibly relocated thousands of individuals belonging to the Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, or Seminole Nations, among others, from the American Southeast to Indian Territory, as central and eastern Oklahoma was then called.

Another example is that, due to long-distance migrations across western North America, the Navajo and Apache Peoples of the American Southwest share some ancestors within the last 1,000 years with some of the Indigenous Peoples of western North America — from as far away as Alaska and western Canada to the northern California coast.

Genetic ancestry tests can impact sovereign Indigenous Nations

We have little control over how our customers may choose to use such information, but we do have a responsibility to minimize harm to the Indigenous sovereignties that could be impacted by the information we provide in this update.

As explored in greater detail in this blog post, many Indigenous scientists, activists, and allies are concerned about the potential for genetic ancestry tests to impact the sovereignties of North American First Nations and Tribes, such as when consumers attempt to access tangible or intangible benefits of membership through their DNA results. This undermines Indigenous Nations' sovereign right to determine membership in the manner they choose.

Finally, and most importantly, our decision at this time to exclude information about the self-reported Tribe or First Nation affiliations of reference individuals was made following the strong recommendation of Indigenous subject matter experts.

We hope that this update will inspire many to learn more about the complex histories and diversity of Indigenous Peoples in North America in a way that also respects how Indigenous Peoples define themselves.

Not necessarily. While there may be some Tribes, Nations, or Peoples more represented in certain regions, the reference groups for these regions were not curated or adjusted based on self-identified or grandparent affiliation. Therefore, some individuals who identify as, for example, Cherokee, may receive a match to the "South Central" region, while others who identify as Cherokee may receive a match to a different region. While there may be some correspondence between the region maps and the current or historical locations of certain Tribes or Nations, historical migrations or forced relocations have obscured patterns of Indigenous biogeographic ancestry in North America.

Geographic regions in this report represent where the descendants of shared common ancestors lived, making it possible that the geographic locations of the common ancestors may have been very different from the regions shown on the map. Major historical migration events have shaped the landscape of genetic variation in North America and may shed light on surprising or unexpected results. One example is what is known as the Trail of Tears (resulting from the Indian Removal Act of 1830), which forcibly relocated thousands of Native American individuals from the Southeast to Indian Territory (as central and eastern Oklahoma were then called).

See also "What Tribes or Nations are included in my region(s)?"

Every Nation, Tribe, or People has its own, distinct membership requirements, and while genetic relationship tests such as paternity tests are used in some cases, genetic ancestry tests are not paternity tests and they are not sufficient evidence to support membership claims. In addition, the technical limitations of these analyses and the ways that DNA is shared across group boundaries make it impossible to demonstrate a direct genetic link to any specific Nation or Tribe. Finally, Indigenous peoples are not discrete or closed genetic groups, and this is not how Indigenous peoples define themselves, meaning DNA is not sufficient to determine such connections.

While we encourage customers to use these results to help learn more about the possible locations and affiliations of their ancestors in North America, it's important to remember that cultural identity is much more than DNA, and to be aware of the cultural and historical nuances of this topic in a way that is respectful of how Indigenous Peoples define themselves.

In North America, the primary requirement for Nation or Tribal enrollment is almost always one or more confirmed relationships with ancestors who were, themselves, documented members of the Tribe or Nation. Though some Indigenous groups in North America have used DNA paternity tests in some cases to determine descent from a documented member, genetic ancestry tests like those conducted by 23andMe are not the same as paternity tests, and are not used by Indigenous sovereignties to determine membership.

Technical limitations

The 23andMe Ancestry feature that provides matches to broad geographic regions in North America cannot provide sufficient evidence on its own that First Nation or Tribal governments would consider meaningful for granting membership or citizenship. Our assignments provide estimates based on genetic sharing between an individual and a reference group, and should not be taken as definitive evidence of descending from a Tribe, Nation, or other People. That's because each reference group includes self-identified representatives from many different Tribes or Nations, and Indigenous Peoples are not discrete or closed genetic groups.

For these reasons, it would be problematic for customers to use their results as evidence in a membership application process, or to access any rights that may be reserved for various Indigenous peoples.

Customers must be aware that membership or citizenship within an Indigenous community cannot be determined with a genetic ancestry test, and it is up to Indigenous peoples alone to define who their members and citizens are.

Understand that genome science impacts Indigenous sovereignties

Beyond the technical limitations of our analyses, it's important to remember that a genetic ancestry estimate is not always the same thing as one's cultural, legal, and/or historical connections to a particular people, place, or nation. One's cultural identity is a combination of many things, and may include: a community connection and recognition, speaking a language, place of residence, genealogy, lived experience, as well as how one self-identifies (of which genetic ancestry testing results may be a small part).

A complex history of exploitation has made it necessary for sovereign Tribal governments to establish policies that safeguard their sovereignty, cultural heritage, and economic resources, particularly when determining who is eligible for membership. Genome science is no exception to this history.

In her book, "Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science," Dr. Kim TallBear explains, "Tribal communities sometimes feel they are under assault by people with tenuous or nonexistent connections to their communities yet who want access to cultural knowledge or to cultural sites for personal identity exploration and sometimes for profit."

Read more about this topic in "Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science" by Kim TallBear

Yes, written and visual content (including FAQs and educational information) — as well as details of the research and development for this feature — were reviewed by Indigenous and non-Indigenous subject matter experts whose feedback and suggestions were incorporated.

Our ability to address every potential concern is limited by the fact that there are many diverse Indigenous cultures and viewpoints in North America. However, we worked to address concerns shared with us by reviewers and to include any suggested content. These subject matter experts provided review to 23andMe because they wished to mitigate potential harm to Indigenous peoples.

Many Indigenous leaders, scientists, and allies are critical of genetic ancestry testing, in particular where it relates to Indigenous American ancestry, for a number of reasons, including:

- the potential for customers to misinterpret results,

- the potential for customers to use their results to misappropriate Indigenous belonging,

- confusion about the distinctions between genetic ancestry results and citizenship within Indigenous Nations and how this confusion harms Indigenous sovereignties,

- the ways that genome technologies can be used to redefine Indigenous Peoples as biological groups or races instead of sovereign peoples and nations, and

- a history of extraction and exploitation of Indigenous peoples in genome science.

By being transparent about the methods used, emphasizing the diversity of Indigenous American Peoples, and providing education about the complexities of the cultural and legal processes through which Indigenous Peoples define themselves and their members, we hope that this feature will have a net positive impact on the discussion while allowing customers to gain insights into where their ancestors may have lived in North America.

Understanding the science

We compare a customer's DNA that is predicted to have been inherited from an Indigenous American ancestor to the DNA of individuals in the reference groups. If a customer has DNA that matches multiple individuals in the same reference group, and a sufficient percentage of their genome as a proportion of their total Indigenous American DNA is covered by these matching DNA segments, we can report the region to the customer as a "match," with "likely" or "highly likely" confidence.

To receive a "highly likely match," a larger percentage of the customer's DNA must match the reference group's DNA than is required to receive a "likely" match. A "likely" match means the customer has met a threshold of shared DNA that corresponds to 50–80% confidence that the match is the most correct match. A "highly likely" match means the customer has met a threshold of shared DNA that corresponds to greater than 80% confidence that the match is the most correct match.

The majority of customers receiving matches will only receive a match to one geographic region, though some customers may have matches to multiple regions. A match to a region simply means that the customer shares DNA with reference individuals for that region.

Remember, this result cannot confirm affiliation with any Tribe, First Nation, community, or group.

To begin building our reference panel, we selected research-consented 23andMe customers who had more than 5% Indigenous American genetic ancestry, and indicated in their Family Origins survey that at least one of their grandparents was affiliated with one North American Indigenous Tribe, Band, Sovereignty, First Nation, or other community.

Next, to uncover geographic patterns of Indigenous ancestry in what is now the US and Canada, we removed individuals from the analysis who shared large amounts of DNA with people whose grandparents were born in Mexico, Central America, South America, or the Caribbean.

At this point, using only DNA estimated by Ancestry Composition to most closely match 23andMe's "Indigenous American" reference panel, we identified groups of individuals who share higher levels of DNA with each other than they do with others in the analysis. These genetic groups became our reference groups for this feature, and we then are able to compare customers' "Indigenous American" DNA to the DNA of individuals within these reference groups.

Finally, we generated maps based on where the individuals in these groups told us their grandparents who identified as Indigenous American were born.

The map outlines associated with your region matches were created using information provided by the individuals in the reference groups about where their Indigenous grandparents were born.

These regions represent where the descendants of shared common ancestors lived, making it possible, and in some cases likely, that the geographic locations of the common ancestors may have been different from the regions shown on the map. Major historical migrations and other events may shed light on surprising or unexpected results.

The individuals who comprise the reference groups told us which of their grandparents identified as having ancestors among the Indigenous peoples of North America. Many of the reference individuals also told us where those grandparents were born, and we were able to use that information to define the following 8 geographic regions that correspond to the genetically defined reference groups:

Alaska

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as Alaska, as well as some parts of western Canada.

Columbia River Basin

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as Washington, as well as some parts of southwestern Canada, northern Idaho, and northern Oregon.

Southwest

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as New Mexico, as well as parts of Oklahoma, southern Utah and Colorado, and eastern Arizona.

Great Basin & Lower Colorado Basin

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as Nevada and eastern California, as well as parts of Arizona and southern Idaho.

Great Lakes and Canada

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as the Upper Midwest of the U.S., including Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, as well as some parts of North Dakota, western Montana, Oklahoma, northern Indiana, northern Illinois, eastern Kansas, and central and southern Canada.

Plains

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as South Dakota, as well as some parts of Oklahoma, North Dakota, eastern Montana, southern Minnesota, and northern Nebraska.

Northeast

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as New York, as well as other U.S. states in the Northeast. Some individuals' grandparents were born in parts of the Midwest and Oklahoma.

South Central

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as Oklahoma, as well as parts of southwestern Missouri, western Arkansas, southern Kansas, northeastern Texas, southern Louisiana, southern Alabama, the Florida Panhandle, and southern Mississippi.

Match strength simply reflects our confidence in reporting this result to you, and should not be used as a proxy for similarity to a group.

For a given region, we indicate our confidence in the result, reported as "likely match" or "highly likely match," corresponding to confidence thresholds of 50%–80%, and 80–90%+, respectively. If we are not able to detect a genetic match to a region with confidence, we report this as "not detected." These confidence thresholds are the same as the confidence thresholds we use to report “likely” and “highly likely” matches to other recent ancestor locations within the 23andMe Ancestry experience.

For example, a confidence threshold of 80% means that, during testing stages, 20% of individuals who are matched to that region did not indicate that they have Indigenous ancestors who lived in that region. This may be due to genuine errors, shared common ancestry among regions, or the individual may have not known (or not reported) all of their ancestral affiliations. It could also be the result of more recent migration and admixture.

These geographic regions represent the location of the descendants of shared common ancestors, making it possible, and in some cases likely, that the geographic locations of the common ancestors may have been different from the regions shown on the map. Major historical migrations and other events may shed light on surprising or unexpected results.

Finally, Indigenous peoples are not discrete genetic groups and are not defined on the basis of biology alone.

By examining grandparent birth locations within each of the genetic groups, we defined 8 geographic regions (see "How did you determine these Indigenous American regions?"). The following regions correspond to places in what is now the U.S. and Canada where many of the individuals within a given genetic group say their ancestors lived:

Alaska

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as Alaska, as well as some parts of western Canada.

Columbia River Basin

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as Washington, as well as some parts of southwestern Canada, northern Idaho, and northern Oregon.

Southwest

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as New Mexico, as well as parts of Oklahoma, southern Utah, southern Colorado, and eastern Arizona.

Great Basin & Lower Colorado Basin

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as Nevada and eastern California, as well as parts of Arizona and southern Idaho.

Great Lakes and Canada

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as the Upper Midwest of the U.S., including Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, as well as some parts of North Dakota, western Montana, Oklahoma, northern Indiana, northern Illinois, eastern Kansas, and central and southern Canada.

Plains

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as South Dakota, as well as some parts of Oklahoma, North Dakota, eastern Montana, southern Minnesota, and northern Nebraska.

Northeast

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as New York, as well as other U.S. states in the Northeast. Some individuals' grandparents were born in parts of the Midwest and Oklahoma.

South Central

- Grandparents of individuals within this genetic group were primarily born in what is now known as Oklahoma, as well as parts of southwestern Missouri, western Arkansas, southern Kansas, northeastern Texas, southern Louisiana, southern Alabama, the Florida Panhandle, and southern Mississippi.

These regions represent where the descendants of shared common ancestors lived, making it possible, and in some cases likely, that the geographic locations of the common ancestors may have been different from the regions shown on the map. Major historical migrations and other events may shed light on surprising or unexpected results.

No. The strength of a match to one of the eight North American regions is not the same as a customer's Indigenous American percentage in Ancestry Composition.

Here’s an example:

According to Ancestry Composition, 10% of John's DNA is Indigenous American and, in addition to that, he has a "likely match" to the region called "Columbia River Basin."

This does not mean that all of John's Indigenous American ancestors must be from the Columbia River Basin and Pacific Northwest. While this is possible, it is also possible that we were unable to identify matches to other regions with confidence at this time. In other words: it's possible that John has some Indigenous American ancestors from the Columbia River Basin, but many more from another region.

To view our estimate of the percentage of DNA you inherited from an Indigenous ancestor, you can see this in your Ancestry Composition report (listed next to "Indigenous American") or at the top of your Indigenous American detailed results view (below the map on the mobile view, or to the left of the map if viewing your results on a desktop).

The match strength we report for a more specific region can be a starting place for customers to learn more about where their ancestors may have lived, but it says nothing about how much of someone's genetic ancestry is from that region. That's because "match strength" is simply the confidence with which we are able to report a match, and it depends on many factors, including the number of reference individuals for each region.

Furthermore, the genetic ancestry percentages we report are predictions only, and these predictions change as the reference databases and algorithms change, so that the result you see today may not be the same result we report for you in the future.

Over time, as we increase the number of reference individuals, results may change to reflect these updates. We will continue to work to improve this report and our predictions. The research we do is powered by research-consented individuals' answers to the Family Origins survey.

Over time, as more people with Indigenous American ancestors join 23andMe, customers' results may change. In the future, this may include more regions in the Americas as well. However, customers with ancestors from the Caribbean, Central America, and South America may already be able to see hints about their more recent ancestor locations in the section of their Ancestry Composition results called "Recent Ancestry in the Americas."

For now, customers with DNA estimated by Ancestry Composition to be of Indigenous American origin — who consent to participate in 23andMe research that supports this feature — can fill out their Family Origins survey.

Unexpected results

We understand that seeing an unexpected region can be confusing, but it's important to remember that this is a prediction based on our current reference database and algorithms, so a match to one of these regions simply means a minimum threshold of DNA matching to the DNA of reference individuals has been met.

DNA results are not necessarily going to match what you know about your family history. There are a few reasons customers could see a region they do not expect based on their family history:

- Historical migrations or forced relocations: By chance, a customer might get a match to a region that is not consistent with their known family history because of historical migrations or forced relocations of Indigenous Peoples that resulted in shared ancestry among the different regions. Geographic regions in this report represent where the descendants of shared common ancestors lived, making it possible, and in some cases likely, that the geographic locations of the common ancestors may have been very different from the regions shown on the map in a customer’s report. Indeed, major historical migration events have shaped the landscape of genetic variation in what is now the U.S. and Canada and may shed light on surprising or unexpected results. One example is what is known as the Trail of Tears (resulting from the Indian Removal Act of 1830), which forcibly relocated thousands of Native American individuals from the American Southeast to Indian Territory (as central and eastern Oklahoma was then called).

- Limitations of the 23andMe reference panel: The confidence with which we are able to report a match strongly depends on the number of individuals within a reference group, as well as on how genetically similar the individuals are to each other within that reference group. So, for a large, very genetically similar group, it tends to be easier to identify genetic matches with higher confidence. For smaller, less genetically similar groups, it tends to be more difficult to identify matches. Over time, as we increase the number of reference individuals, results may change to reflect these updates. We will continue to work to improve this report and our predictions. The research we do is powered by research-consented individuals' answers to the Family Origins survey.

- Incomplete knowledge of family history: Results may reflect ancestors from different regions than customers are aware of based on their family records. This analysis may identify DNA from both recent and more distant ancestors, so it’s possible to have an unknown Indigenous American ancestor who is from a different region than might be expected based on your family history. Remember, just 6 generations ago you would have 32 4th-great-grandparents.

- Prediction error: These results are estimates, meaning that some matches may not be perfectly in line with customers' self-reported ancestry.

It is important to understand that Indigenous peoples and the geographic regions we have defined here do not represent discrete or closed genetic groups. In other words, DNA is shared between groups and across space in ways that may or may not neatly correspond with the categories we have defined here. Because Indigenous peoples are not closed genetic groups, and do not define themselves as such, DNA cannot produce concrete or precise connections to Indigenous peoples.

In the end, it is up to Indigenous peoples alone to define who their members are.

If someone doesn’t share the minimum amount of DNA with reference individuals, or the percent of their Indigenous American genetic ancestry shared with reference individuals does not pass our confidence thresholds, then they will not see a match to that region. Keep in mind that we may be able to match customers to additional regions in the future as our database grows.

Fewer than 10 percent of customers with some Indigenous American genetic ancestry will receive a match at this time, though this number may be higher for customers with known Indigenous ancestors from North America. For this update, we focused on accuracy and ensuring that there were as few false matches as possible. As a result of this approach, there will be some individuals with known Indigenous American ancestors from North America who do not receive a match to any region at this time. There are also Tribally affiliated and First Nations peoples who have no detectable DNA from Indigenous peoples prior to colonization. Because Indigenous peoples are not discrete genetic groups, and do not define themselves as such, this product will not be able to detect non-genetic relationships. This underscores the complex ways in which Indigenous peoples define themselves as well as the limitations of DNA technologies in describing them. Indigenous belonging is more than DNA.

We understand that not seeing an expected match can be confusing, but our ability to match someone to a region based on DNA is only as good as the size and diversity of the reference groups and algorithms used to predict them. Over time, as more people with Indigenous American ancestors join 23andMe, customers' results may change.

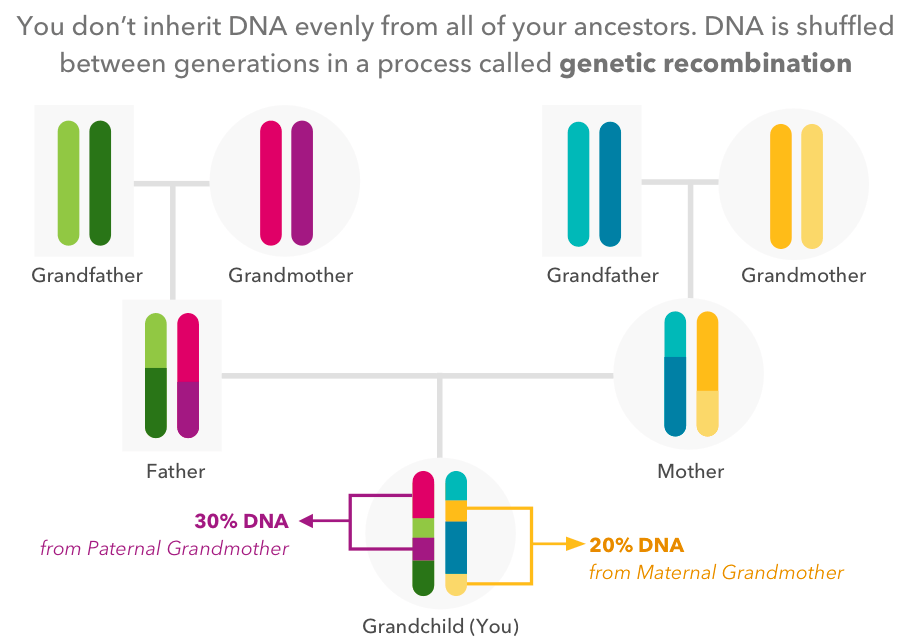

DNA is randomly shuffled between generations in a process called genetic recombination. As a result of recombination, the farther back in your history you look, the less likely you are to have inherited DNA directly from every single one of your ancestors. This means that you can be directly descended from someone indigenous to the Americas without having inherited any DNA from them. But, there's another reason someone might not have "Indigenous American DNA": In North America during the 19th and 20th centuries, white settlers or their descendants sometimes misattributed an ancestor as Indigenous. This may have been to justify a more native-born "Americanness" or to absolve one's family of blame for colonialism, and these stories are still passed down through families to this day.

If your family has a story like this but there's no documentation, it doesn't necessarily mean those stories are wrong. Just remember: whether or not you have Indigenous American DNA, your genetic ancestry may not be consistent with your cultural identity, genealogy, or community connections. Indigenous belonging is more than DNA.